April 10, 2021

Telehealth ban for VAD makes life and death difficult

A 2005 Federal Australian Government Telehealth ban for VAD makes life and death difficult in the country for anyone who wants to speak to their doctor or Exit using the telephone, fax, email or the Internet. This is a law that belongs in the likes of Nth Korea or China. But it continues to have effect in Australia!

Terminally-ill regional residents face extra access hurdles due to a Howard-era federal law that bans them using telehealth consultations for the process.

Australia’s foremost euthanasia advocate Philip Nitschke wants the federal government to allow telehealth consultations.

Carol Onley, 66, is dying. After 18 months of Victoria’s voluntary assisted dying program, 224 Victorians have ended their lives.

She’s leaving behind unfinished paintings in her “she-shed”, a loving extended family, and a supportive partner.

“More than 10 years ago now, I had my first diagnosis of lung cancer which was amazingly shocking,” she said.

After a successful surgery and course of immunotherapy, Carol got back to living.

“But in 2019 I had some symptoms which seemed quite unusual, so I went and had a CT scan, and yes, those little nodules had now absolutely exploded.”

After a lifetime as a mental health nurse and a smoker, Carol knew what was ahead of her.

“Through my nursing career I was quite aware of voluntary assisted dying (VAD), that it had become available to people in my position,” she said.

“[At the] beginning of this year, I’ve embarked on that program.”

Despite breathlessness and fatigue, Carol is enjoying her life as she started it: on the farm.

Under Victoria’s VAD program, two doctors need to independently verify the patient is of sound mind and has less than six months to live for a physical illness and 12 months for a neurological condition.

But living in regional Victoria has made the process more difficult.

“I was actually shocked to find in Gippsland there were only two doctors available who could make that assessment,” Carol said.

There are just 76 doctors in regional Victoria trained to help terminally ill people access the VAD program.

“I have family, I have good supports who’ve helped me all through this and they can take me to wherever I’ve needed to go,” Carol said.

“I’ve just wondered about people who live further afield from Orbost or Bairnsdale, if you don’t have quite so much good access to supports, how do they access the program?

“There just seem to be some barriers that are a little too difficult for people to overcome.”

Victoria’s progress

Victoria’s VAD program, which came into force in 2019, was the first state-based program in Australia.

In a statement, a Victorian government spokesperson said the legislation was leading Australia.

“Our voluntary assisted dying laws are giving Victorians with an incurable illness at the end of their lives a compassionate choice,” they said.

“This service has been expanded through regional Victoria and we continue to encourage more medical practitioners to become involved to allow greater access across the state.”

But the board charged with reviewing the program found there were “limited numbers” of GPs trained to consult on euthanasia in far east and west Victoria.

The Voluntary Assisted Dying Program Review Board says there are “limited numbers” of practitioners in the east and west of the state who can help terminally people access the program.

Process ‘takes time’

A former Justice of the Supreme Court of Victoria, Betty King, is the chair of that board.

Former Victorian Supreme Court Justice Betty King says Victoria’s legislation is “very conservative”.

“[We’ve recommended the government] encourage more specialists to do the training and sign up for the program, it’s a busy practice and there is so much for most specialists in regional Victoria to do, without this additional time,” Justice King said.

“It does take time. This is not an easy and quick process.

“It’s certainly been one that’s designed to be safe, and when you have a lot of safeguards built in it does take time, so it’s very difficult for them to take that time out of their practice.”

Victoria’s Voluntary Assisted Dying board is set to table its final report on the program in Parliament in August.

Telehealth ban amplifies inequity

But as other states bring in VAD programs of their own, there is another problem facing regional Australians trying to access euthanasia.

“So much now in medicine, particularly regionally, depends upon telehealth; unfortunately telehealth is not permitted for VAD, because federally some legislation was introduced to prevent [euthanasia advocate] Dr [Philip] Nitschke from sharing methods of suicide (editor’s note – voluntary euthanasia) online,” Justice King said.

Breaking these laws could incur fines of up to $222,000 for individuals or $1,110,000 for businesses.

“It potentially prevents our doctors in Victoria from being able to use telehealth to discuss things and talk to patients and that really is a major inhibitor,” Justice King said.

“We have called on the Commonwealth to just exempt voluntary assisted dying from it, because we are a government, organised, legal process, but so far they have not been willing to do so.”

In a statement, the federal government said people should have access to quality palliative care.

“The government has no plans to amend the suicide-related material offences in the Criminal Code (passed 2005).”

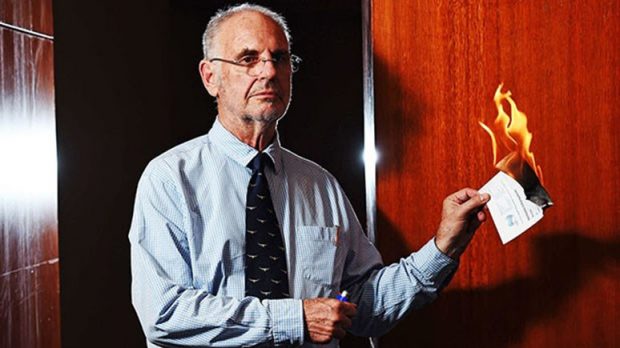

Voluntary euthanasia advocate Philip Nitschke sets alight his medical certificate at a Darwin press conference.

Dr Nitschke, once investigated for testing the purity of a drug used in a terminally ill man’s suicide, said the introduction of the amendment in 2005 was targeted.

“It’s often a piece of legislation that I think people aren’t aware of, and it was an insidious introduction that came in under the Howard government with Philip Ruddock as Attorney General, that I think the public were never really aware they were having a pretty basic and fundamental freedom eroded,” he said.

As more states begin their VAD programs, Dr Nitschke said the federal government needed to change the code to ease the burden on regional Australians.

“It’s certainly something that needs addressing if we’re to see uniform legislation and equal access to what’s available in these new end of life pieces of legislation sweeping across Australia,” he said.

West Australia

In geographically vast Western Australia, the tyranny of distance will rule regional access when its voluntary assisted dying program begins in June.

Western Australia’s Australian Medical Association president, Andrew Miller, said more resources would be needed to compensate for the ban on telehealth.

“It’s the same situation that there is in Victoria, things have to be put in place to enable face-to-face consultation, they’re going to have to put some resources into that,” Dr Miller said.

The Australian Capital Territory, Northern Territory and Norfolk Island have not been able to make laws on euthanasia since the federal government quashed the NT’s program in 1997.

Two weeks ago, the ACT’s health minister and opposition leader passed a motion of “profound disappointment” that the federal government was continuing to block euthanasia law.

A statement made by the federal government in response said:

“The government currently has no plans to repeal the Euthanasia Laws Act 1997.”

ACT Health Minister Tara Cheyne said the federal government’s ban on territories making euthanasia laws was a human rights issue.

“There is a separate issue here from voluntary assisted dying — it is about democratic rights and we’d like to see the call coming from right across federal parliament,” she said.

Carol and her siblings. Pat, her older sister (left), passed away in 2015 from Motor Neurone Disease.

‘All I really want is to feel comfortable’

Carol does not know when she is going to take the drugs that will end her life.

It is a delicate balance.

“You’ve gotta be with it enough to do it, so I can’t let the situation roll on too far, I’ve got to have enough dexterity to take the medication,” Carol said.

“It’s very confronting.

“I’ve been with family members who’ve passed away … my sister had Motor Neurone Disease, she had to go right to the end of that disease because there were no other options for her.”

After a life of adventure, service and love, Carol admits she’s a little bit of a “control freak”.

“I am so grateful to have the opportunity to die with dignity,” she said.

Read Exit’s Deliverance newsletter from December 2005 for background on why a 2005 Telehealth ban for VAD makes life and death difficult in the country some 16 years later.