November 6, 2022

Suicide and what becomes of the broken hearted

‘Suicide and what becomes of the broken hearted’ … reports Christine Middap from News Ltd’s The Australian newspaper.

Note – Exit has included editorial comment by Fiona Stewart @ Exit Fact Checking

*****************

Annah Faulkner was not dying. She wasn’t even ill.

But the award-winning novelist was sad, grieving the loss of a husband she adored while trying to present a brave face to friends and family.

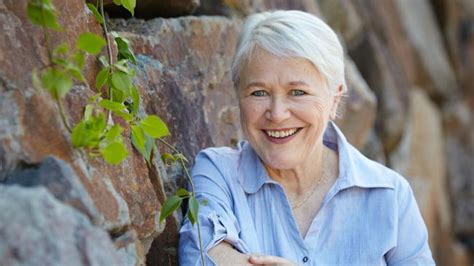

With short-cropped hair and a steady blue gaze that reflected her forthright manner, she was fit for her 72 years and regularly travelled between her homes in Tasmania and Queensland, a comfortable lifestyle that gifted her endless summers.

She enjoyed being with friends, reading and walking, and as the months marched on from Alec’s death, those closest to Faulkner thought that time might finally be doing its thing, smoothing the sharp edges of her grief.

But life, she said, felt empty without Alec. She’d never had children, and despite her small group of friends and an older brother in Brisbane, Faulkner was lonely.

[Annah did say she was lonely: another extraordinary show of courage on her part. Old age is lonely. Friends and life partners die, your body a source of never-ending decline. That is what life and death are, sadly, about.]

Past successes – her 2012 debut novel The Beloved was short-listed for Australia’s premier literature prize, the Miles Franklin, and won the kibble literary award – no longer meant much.

[The journalist never met Annah Faulkner. Nor was Philip Nitschke interviewed for comment for this article.]

“I am grateful for friends and for the life I’ve had,’’ she wrote earlier this year. “But whatever meaning I derived from that life, including past work, interests, and hobbies, disappeared with Alec.”

And so by March this year, seven months after Alec died at their Sunshine Coast home, she concluded: “my life is over, and for me that’s perfectly ok.’’

Where some might have sought professional help or support from friends, Faulkner instead found comfort and advice at the Tasmanian chapter of Philip Nitschke’s assisted suicide group Exit International.

Here, she found new “vibrant, funny” friends who, she said, understood her and did not judge.

“If not for my friends at Exit international I would be unspeakably lonely,’’ she said.

From that early contact with Exit, in December, she appeared set on a course, pretending she was okay to friends and family while meticulously planning her suicide and regularly chatting with Exit’s Tasmanian co-ordinator Kay Scurr, a recently retired nurse and counsellor who made no effort to alter her course.

In early March, with a photograph of Alec and her childhood doll Roberta by her side in her Launceston apartment, she sent a final email to Scurr. She was ending her life.

Scurr’s job was not to intervene but to notify police who duly attended the scene, seized Faulkner’s computers and phone and interviewed Scurr (it is believed her death is before the Tasmanian coroner).

Providing Guidance

While Australia’s lawmakers and politicians have been wrestling with voluntary assisted dying (VAD) legislation for the advanced terminally ill, Nitschke’s organisation has been operating in stark contrast to the protections and limitations of the hard won laws now in place in every state.

[Christine Middap seems to forget it was Exit Founder, Philip Nitschke, who was critical to the implementation of the Northern Territory’s Rights of the Terminally Ill Act in 1996. If anyone knows about hard won laws, it is Philip]

Sick, sad or simply tired of living, Nitschke’s position is clear: any rational adult has the right to dispose of their life, including those who are depressed and mentally ill, prisoners serving life sentences, and bereaved widowers or widows, such as Faulkner.

He has said his organisation draws the line at providing information to children.

[Exit actually has an age limit of 50 years, so it’s a bit more than ‘children’. But there are always times when young people need access to the best, end of life information. Rhys Habermann is a pertinent case in point.]

The former Darwin GP is contemptuous of the new “beg and grovel” laws and his organisation is still providing guidance on DIY end-of-life methods with few apparent checks and balances.

[If Annah Faulkner had elected to travel to Switzerland for a lawful assisted death, her death would have attracted no interest. What is it that makes some journalists so narrow-minded?]

Now based in the Netherlands, Nitschke will next week begin a three-month Australian tour dedicated to Annah Faulkner, consisting of a series of four-hour workshops for those aged over 50, the seriously ill, “or by special arrangement.”

[Philip lives in the Netherlands because it is at the forefront of the right to die debate. Only in the Netherlands is there an active and progressive discussion about the rights of the over 70s to end their lives when they feel the time is right to go.]

Faulkner had spoken in general terms with her friends and brother Peter about Euthanasia but they had never considered her a soldier for the cause and she had not mentioned joining Exit.

However, she left a “not inconsiderable legacy” in her will to the organisation, according to Peter, and in the months before her death penned a three page pro-suicide manifesto now being used by Exit to trumpet its cause.

[Exit had no prior knowledge of the bequest. A lot of people say they will make a bequest, in reality few do.]

[No body is ‘trumpeting’ any cause. Annah left a letter she asked Exit to publish. Should Exit have told her to bugger off? Christine Middap, please tell Exit what they should have done with Annah’s beautiful farewell letter?]

The letter has been picked up by others and posted on the youth-oriented video platform Tiktok.

[So what if Annah’s letter has been posted on Tiktok as an audio file? It is a beautiful, thought-provoking piece of writing. It’s actually quite well done. Besides, Janine Hosking’s ‘Mademoiselle and the Doctor’ documentary – also about an older woman who did not want to live on – is taught in Australian schools and was awarded by the Australian Teachers of Media (ATOM). What is the problem? Or is this innuendo?]

“Not everyone who wants to die is mentally unhinged,’’ Faulkner wrote, describing the “grieving widow’’ as a cliche and dismissing the idea of grief-induced depression.

“No individual or group has the spiritual or moral authority to dictate how and when people should die,’’ she added, while advocating for legal access to the death drug Nembutal (which she did not use to end her own life).

The Tasmanian criminal code, like other state laws, makes it an offence for any person to instigate or aid another to kill themselves, but in practice the courts tend to take a compassionate approach when people aid or kill terminally ill family members who want help to die.

In contacting Exit, Faulkner found a welcoming, friendly, affirming atmosphere and Scurr, 69, says they quickly became friends.

She says her organisation offers knowledge, books and information to its members, who may not in fact be terminally ill, but she adds in relation to Faulkner: “I had nothing to do with the actual suicide.

“When she first met me she had already put everything in place … she sourced all the equipment,” Scurr says.

Knowing that Faulkner had recently lost her husband, and was perfectly healthy, was there a moment when she suggested she give it more time to deal with her sadness?

“Never. No. I wasn’t going to patronise her. She was very assertive and very confident … it was her business, her choice.”

Two of Faulkner’s Launceston friends, who asked not to be named, said they were shocked by her suicide and by the strongly-worded public letter she left behind.

“Quite a few of us are very angry,’’ says one, who’d had dinner with her in the week before she died.

“Because there was nothing wrong with her, she wasn’t sick. There was no sign of depression or anything.” This friend has lost loved ones, had her own health worries. She was not without sympathy for Faulkner but believes that in the face of life’s adversities “you’ve got to battle on”.

Had Faulkner revealed the depth of her despair, said another friend, she would have discussed it and suggested getting some help.

But on this point her brother, Peter (who asked that his surname not be published), is clear: “counselling wouldn’t have helped. She was a strong-minded woman.

By the time she reached out to Exit, her mind would have been made up, and made up on her grounds and no one else’s.’’

No reason to live

Though recently diagnosed with motor neurone disease, Alec’s death in August last year at their Sunshine Coast apartment at age 84 was sudden – Faulkner hadn’t expected him to go the day after she brought him home from hospital.

They’d been married more than 30 years and had a loving bond and a shared love of travel and fine dining.

In the days and weeks after his death, heartbroken and overwhelmed with the task of sorting out their affairs, Faulkner would remark that she had no reason to live.

“But it was never to the point where I thought she would take her own life,’’ says a friend who last spoke to her on the day she died.

Peter says that he had never seen his sister so low but by Christmas she appeared to have turned a corner. “She wasn’t the grieving semi-crushed person that she had been since alec’s death.

She had a lot of positive energies. So I thought ‘it’s all good’. She put up a marvellous front,” Peter, a retired lawyer, says.

He says he would have talked with her, and listened, if she’d divulged her plans.

“But ultimately I would have respected her wishes. she was a strong-minded woman,’’ he repeats, adding that he agrees with the sentiments expressed in her open letter.

“We have too much government in our lives generally speaking and they try to control our deaths as well. Damn them all, I say. That’s why I have great respect for what Annah did and the manner in which she carried it out. ii wasn’t a spur of the moment thing, a sudden emotional wave … it was well thought out and considered over a long period of time.

“In her letter to me she said ‘please don’t be angry’ and I’m not. I understood why she did what she did.”

Professor Ian Hickie, former chief executive of Beyond Blue and the co-director of the University of Sydney’s Brain and Mind Centre, says people are often highly vulnerable following the death of a loved one.

“It’s a very difficult period of often three to 12 months for many people,” professor Hickie says.

“They can feel that a part of their life has ended, but that doesn’t translate into their whole life has ended. or that there are no other options, or that they will not form other relationships or continue to be a very important part of our society.

“People in these situations often find new meaning, form new relationships, contribute in other ways, beyond the period of bereavement,” he says.

“Reinforcing the idea that simply because you’re old or simply because a relationship has ended that this is the appropriate time to exit, that’s what I find most troubling about the whole Exit movement.”

[The counter-view is used to give a piece ‘balance’. To recruit a representative whose professional viewpoint has been and always will be one that sees all suicide as ‘always a mental illness’ is lazy journalism. It would be good to add some nuance to this debate.]

On the fringe?

Exit international’s advocacy for open slather right-to-die measures for any rational adult has put it on the fringe of the movement. Broadcaster Andrew Denton, who founded Go Gentle to advocate for VAD, distances his group from Nitschke’s but doesn’t entirely disavow its views.

[‘open slather’ – ouch! Here is Exit’s screening approach. The organisation eagerly awaits the upload of the journalist’s photo ID via video to prove her age 🙂 Click here to verify your age and ID]

“We don’t have any association with Philip and none of the state Dying with Dignity organisations do either. It’s not where our conversation is at all, although we acknowledge that for some Australians it’s a very important conversation,’’ he says.

Denton says Go Gentle works at the centre of the system with hospitals, doctors and parliaments. “We think that’s the right place to be for social change. Our view very strongly is that the VAD laws were very hard won, fiercely debated, and need to work well.

“These other conversations will happen naturally as we age as a society and it may well be that future parliaments and future societies decide to go further than Australia has at this point.

“Philip Nitschke isn’t all wrong and VAD laws aren’t all right but there are competing balances,’’ he says.

Denton says Go Gentle’s job now is to protect the laws against those who would have them repealed, to be part of the review process, and to advocate for changes where the laws impede access for the eligible.

“We want to see that the laws work better for the people for who they are intended,’’ he says.

Victorian emergency physician Dr Stephen Parnis, an opponent of the VAD laws, says that five years after the legislation was first passed in Victoria he’s “not surprised the envelope is being pushed on this”, adding: “I guarantee you there will be pressure to expand the scope of eligibility.”

As for Nitschke, Parnis describes him as a zealot. “He believes he’s doing the right thing but doesn’t have any ability to see that what he’s doing is extreme.”

‘So much to give’

In the months after Alec’s death, Faulkner spoke to friends about ways to fill her days.

She thought about volunteering and says she investigated various groups.

“Palliative care, I feel, would be worthwhile but for various rules and reasons all I could get was housekeeping. No reading to, listening to or chatting with patients,’’ she said.

A talented writer – her second book, The Last Day in the Dynamite Factory was generally well reviewed but failed to reach the heights of her debut The Beloved – she’d been working on another book before her husband’s illness.

[Creating a vision of a depressed, failed writer? Please give the woman some agency.]

“She had so much to give,’’ says one friend.

Faulkner left instructions in her will that all her unfinished works should be destroyed. the only recent writing that survived was her manifesto, written over weeks, that she wanted Exit to publish.

She called it ‘An Open Letter to Australia and the World.’

Christine Middap is associate editor and chief writer at the Australian. She was previously editor of The Weekend Australian magazine for 11 years.

While best known for her fashion lifestyle journalism, Middap is no new comer to the end of life choices debate.

She was the editor who oversaw the considerable public reaction to Australian writer Nikki Gemmell’s writing on the death of her mother Elayn Gemmell (who was also an Exit member).

Middap knows that death sells. However, her reporting on Annah Faulkner shows little understanding of the cutting-edge – and most certainly the future – of the global end of life choices debate: how will the world deal with the post-70s generation (formerly the baby boomers) who say they have had enough and that now is the time to go?