January 17, 2021

Selling Coals to Newcastle? The Dutch Discover the Swiss Option

Always on time, he is ready in the morning in the hall of his apartment.

Kees Kentie (87 years) is ready in every way.

He was counting down the days in the past week.

Everyday actions are against him. Shaving: it’s exhausting. He’s looking forward to his last shave tomorrow.

Today, July 22, 2020, Kees is going to Switzerland.

Tomorrow he will die there. July 23.

By coincidence the same day as his great love, Han, almost forty years ago.

At seven o’clock his neighbor, Aad Beijersbergen, is at the door. Beijersbergen lets himself in with his key.

They greet each other. Kentie steps into the hall and no longer cares for his apartment in The Hague, with its carefully collected antique furniture.

Beijersbergen talks about the weather. Fortunately it is beautiful today.

With his neighbor, Kentie descends those detested stairs from the second floor for the last time.

Every time he is afraid of breaking something, of ending up in hospital. To be in pain. And above all: to no longer be able to choose his death for himself.

At Beijersbergen’s kitchen table, on the ground floor, he waits for the car to Schiphol. Coffee? Tea? A biscuit?

No, thank you.

At the beginning of 2020, Kentie told his story in Trouw.

He did not want to go on.

In fact, after Han’s death – they’d been together for over thirty years – he had never made any more of life since that time.

Sure, he blamed himself for this, but now that he was old and frail. He said there was nothing to be done with it.

He barely goes out for fear of falling. Kentie has been living with a death wish for years, he says.

Kees was in touch with and trying to get help from the Hague Euthnasia Expertise Centre for two years.

Ultimately, no doctor there would allow him euthanasia. Nor would his GP. In their eyes, Kees’ suffering was not unbearable (as required under Dutch law).

When Kees initially told his story in Trouw it appealed to many readers.

They sent letters and emails.

One woman offered to take him to the Tefaf, the art fair in Maastricht, where Kentie said he wanted to go again.

Another offered to come and play board games with him.

Kentie was warmed by the letters he received.

If he had had their phone numbers he would have called to say ‘thanks’. But no, he did not like activities. Too much hassle, too serious.

And, besides, his ‘death wish’ had not changed.

Moreover, Kees was already working on a different way out. One that would cost him over 10,000 euros – but money is of little value to him.

Kees no longer has family. A few friends and acquaintances will get what he has after he has gone.

In the fall of 2019, after he was rejected from the Hague Euthnasia Expertise, he started looking at other options; with the help of a consultant from the Dutch Association for a Voluntary End of Life (NVVE).

The consultant gave him information about suicide with pills. They talked about the risk that such suicide could fail on its own. Kentie was not much interested in failure.

Switzerland, with its law permitting assisted suicide, remained the only option available.

Switzerland has six organizations that provide assisted suicide, four of them allow foreigners.

In October, Kentie submitted an application to one of those four.

Kees’ friend, Jos Hooimeijer, filled in the web application on his behalf. “You can void it at any time,” emphasized Hooimeijer.

“Nobody will think twice, even if everything has already been arranged.”

[He was told they] said that there would be a place in January 2020.

But time went too quickly. For Kentie that was too soon.

You must be well prepared for death: a lesson he had learned from Farah Dibah, the widow of the former Shah of Persia, which he had read about in an interview in Privé magazine. He must have read the article a thousand times.

Hooimeijer still had thoughts that, maybe, Kentie might not want to die after all. He thought that perhaps he only wanted to know that the option of Switzerland was available in case he should need it.

But by January 2020, it became clear to Hooimeijer (and Beijersbergen) that the postponement was not the same thing as Kees cancelling his appointment.

Kentie spoke very firmly about his plans. Besides, he had deteriorated further physically in recent months. He may well have qualified for euthanasia at home.

But a new euthanasia application was not of interest to Kenie.

Without the help of his friends, Beijersbergen and Hooimeijer realized Kees’ plans would be thwarted.

They knew that even if they didn’t help Kentie, Kees will end his life by stopping eating and drinking.

They knew that Kentie would dread doing something like that. They wanted to spare him that.

Hooimeijer had a good feeling about [the clinic]: the fact that they were so careful with the documentation showed it to be a careful process.

Hooimeijer booked three tickets to Switzerland: for himself, Beijersbergen and for Kentie.

All three were return trips, so that Kentie could abandon his plan until the very last moment.

In the Swiss village of Liestal, Kentie, Hooimeijer and Beijersbergen took rooms at hotel De Engel, as recommended by [the clinic].

In this hotel no eyebrows would be raised if one of the guests just disappeared.

After lunch, [he] visited at the hotel.

Habegger (70) is the chairman of the association and the man who oversees each assisted suicide.

He has the doctor (in his 40s) with him. The doctor will perform assisted suicide. Kentie welcomes the doctor with a wide-arm gesture.

“You’re the man I’ve been waiting so long for”, he says in English.

They talk for over an hour.

In the conversation Hooimeijer submits all papers, including Kentie’s birth certificate and a copy of his passport. There is even an energy bill, to show that Kentie is, indeed, who he says he is.

The doctor does not perform a physical examination.

He has one and a half pages of Kentie’s medical history, as noted by his own Dutch doctor.

The medical records show, among other things, that Kentie is mentally competent: a condition of Swiss law.

There is also a document that summarises Kees’ life. A biography if you like.

From everything Kentie says in the conversation you could see that he was looking only towards his peaceful end, Hooimeijer recalls later.

That Kentie is ‘tired of life’ is explained in the context of the conversation and from the supporting documents. It does not need to be explicitly asked. It was important that Hooimeijer had earlier helped Kentie put his thoughts down on paper.

Half an A4 page long, Kees explained that he was at a time whne he felt that his life was increasingly completed and that he had a fear of further decline. He wanted to stay in control until the very end.

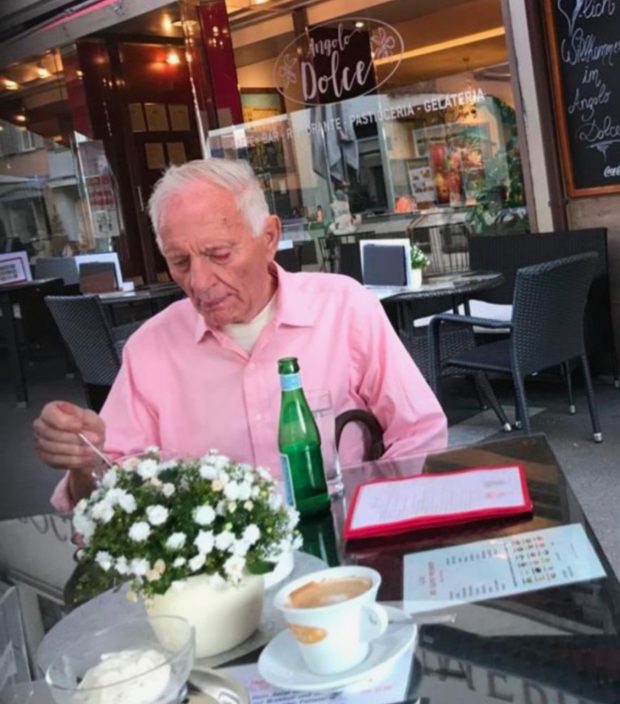

On his final evening Kentie, Beijersbergen and Hooimeijer sit on a terrace in Liestal.

Kentie orders salmon and a glass of beer, finished off with a large fruit slice.

Hooimeijer is surprised that Kees seems so unfazed. “It’s done”, Kentie says dryly.

Kees thinks there is something after death. A place where he will see his husband, Han, again.

The next morning at breakfast Kentie points out the pastries on the buffet table to his to his traveling companions, suggesting they should definitely try them.

How is it possible, Beijersbergen wonders? At 9 o’clock you are eating so well, but in three hours you will be gone.

As the Swiss attendants arrive at the Hotel and sit down for a cup of coffee, the atmosphere is cozy. Kentie asks them questions.

How did they end up in this work? Do they live close by?

At ten o’clock the three Dutchmen drive follow the Swiss by car, into an industrial area.

Here, in an anonymous building, is the clinic. The room is bright with a coffee table and a large sofa. A huge seascape hangs on the wall.

In the back there is a passage to a smaller room where there is a bed. The room is slightly muted. No one else is present, Kentie is the only one who will die here this morning.

Do they want some more time together before proceeding? No, says Kentie.

As they go through a final series of forms, Kentie is impatient. He thinks that this prelude to his death has long enough lasted.

He sits on the bed and the anesthetist inserts the drip. He explains every step. Then a camera is turned on. Kentie has to explain on screen who he is.

“Why are you here?” Asks Habegger. “To sleep in,” says Kentie.

Wrong. Kentie must make it clear that he knows “he is here to die”, explains the Habegger. “To die,” says Kentie.

Is he willing to open the tap to the IV drip? “Oh, yes,” says Kentie. But he finds the wheel of the IV difficult.

Hooimeijer reaches out – seemingly in a reflex – to help, but that is also wrong. Kentie must perform the act completely independently.

The recording starts again. Kentie answers the questions for the third time. He makes eye contact with Hooimeijer and Beijersbergen.

Without words, or any visible emotion, Kees takes the wheel and turns it to open.

Within six seconds, the color is out of his face disappeared. Kees Kentie is no longer alive.

Kees Kentie gave Trouw permission to publish about his death.