January 31, 2021

Religious Bigot Kevin Andrews Loses Preselection

The Fall of Kevin Andrews?

Kevin Andrews – the guy whose private member’s bill in the Australian Parliament (The Euthanasia Laws Act) led to the overturning of the world’s first voluntary euthanasia law – the Rights of the Terminally Ill Act (NT) (ROTI) in 1996 has finally lost Liberal Party preselection in the Melbourne seat of Menzies.

A Catholic extremist, (and well known for his ‘traditional values’ marriage counselling prowess), Andrews once boasted that he had set the Australian voluntary euthanasia movement back 20 years. And he was right.

Why do we highlight the demise of Kevin Andrews now?

This weekend, Kevin lost the vote (pre-selection) in the Australian Liberal Party (Australia’s right wing political party) to continue as their candidate for the Melbourne seat of Menzies.

Kevin will never again represent the electorate of Menzies in the Australian national Parliament.

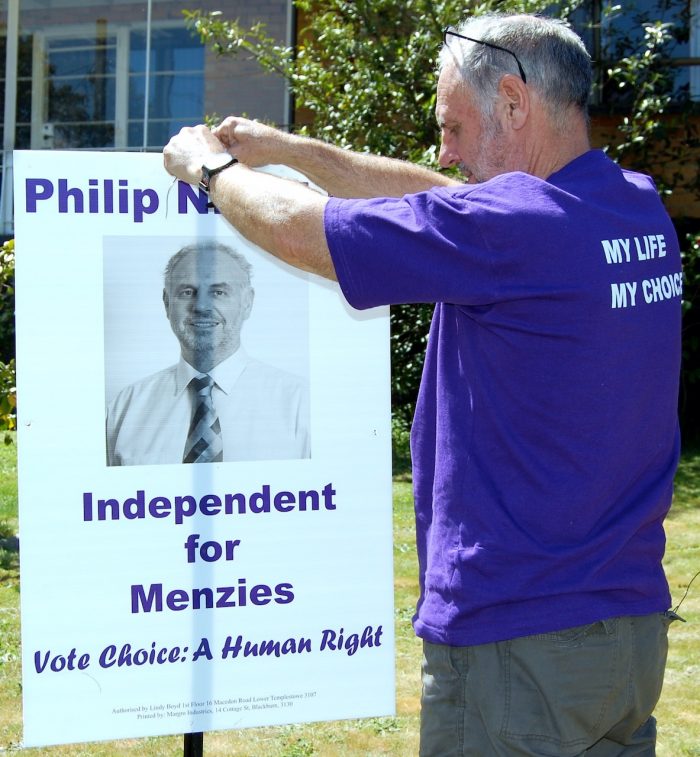

Twice I campaigned as an Independent candidate in Menzies against Kevin Andrews.

In 1997, I forced him to preferences. This meant I came the closest of any candidate during his tenure to beating him. Sadly, Menzies is a safe Liberal seat and so Kevin prevailed.

Until now …

Campaigning against Kevin Andrews in Menzies, 2007

Below is an extract from my book – Killing Me Softly: Voluntary Euthanasia & the Road to the Peaceful Pill – that puts that man and that time in perspective.

How could this happen?

In my mind, strategic and persistent lobbying of politicians could have prevented the passage of the Kevin Andrews Private member’s bill.

I was furious that the state voluntary euthanasia societies were not prepared to do more to save the ROTI Act.

Canberra (Federal Parliament) was able to override the NT legislation through use of Section 122 of our Constitution which grants the Commonwealth the power to make laws for the government of any territory of Australia.

While state laws are preserved, the Northern Territory, Norfolk Island and the ACT are subject to this special power – a power which rides rough-shod over proper, regional democratic processes.

But this is only half the story.

The other half concerns a wide-reaching network of people, many from within the Lyons Forum (the secretive organisation of the far-Right of the Liberal Party) and Catholic Church-based propagandists.

With ringleaders headed by Kevin Andrews but including former Young Labor president Tony Burke – and now member of the shadow cabinet –and Sydney businessman Jim Dominguez, the ‘Euthanasia No’ campaign was well-funded and effective.

In the words of award-winning journalist Michael Gordon, the No campaign was a ‘story of a network [where] all the principals are Catholics – its influential connections, its single-mindedness and the tactics it employed’.

Philip Nitschke, Democrats Candidate Damian Wise & Kevin Andrews – Townhall meeting Doncaster, November 2007

White ants in the media

A second group that set out to undermine the legislation was the national media, most particularly The Australian newspaper in Sydney. As a prominent member of the ‘Euthanasia No’ campaign, the then Murdoch-hack & editor-in-chief, Paul Kelly, openly abused his position at the paper to promote ‘Euthanasia No’, ensuring his personal opposition to voluntary euthanasia was effective in the process.

Kelly’s complicity in the campaign was exposed to me by The Australian’s then Darwin correspondent, Maria Ceresa.

While her Fairfax counterpart, journalist Gay Alcorn, filed stories without bias, Ceresa was increasingly thwarted by the paper’s hierarchy in her coverage of the issues surrounding the ROTI law.

Ceresa would later tell me that unless the story was highly critical of the legislation, the paper would not run it. She felt herself professionally compromised as a result.

White ants in the right-to-die movement

To my dismay, during 1996 I discovered that the right-to-die movement itself was unwittingly helping to undermine the legislation. I knew something was not right as I travelled from state to state during 1996, trying to involve the VE societies, and trying to get them to mount a coordinated campaign to save the ROTI Act.

But the response I received was patchy, and although I managed to get representatives from Queensland, South Australia and the ACT together for a strategy meeting in Canberra, there was little willingness to pool resources and mount a national campaign.

As for the Victorian society, they did not even attend the meeting and argued that it was unwilling to put money into a project that would not directly benefit that State. Later I met with the president, Dr Rodney Syme, and the then executive officer, Kay Koetsier, whereupon they expanded on this view.

Syme explained that while the society was prepared to pay for survey work that could benefit Victoria, there would be no involvement in a national campaign to lobby federal politicians. Koetsier went so far as to claim that the passage of the Andrews Bill could even bode well for Victoria.

When I asked Koetsier to elaborate on this extraordinary claim she said that if the Senate voted in favour of the Andrews Bill, there would be a national outcry.

Then, the Premier of Victoria, Jeff Kennett, would take it upon himself to ‘do the right thing’ for the people of that State, and pass right-to-die legislation. History tells us otherwise. I found Kay’s comments to show a profound lack of judgement.

I told her I didn’t agree and the conversation moved on.

In retrospect, it was little wonder the ‘Euthanasia Yes’ campaign was defeated. Not only was the Commonwealth–Territory power not on our side but the media, the Church and a whole network of powerful and wealthy people pulled out all the stops to defeat the landmark legislation.

Campaigning in Bulleen

The parliamentary word

In an unprecedented occurrence, when the Kevin Andrews Bill was finally debated in the Senate it went on for the best part of four days. The speeches heard in both houses of parliament were some of the most emotional ever made by Australian politicians. While some MPs spoke about the rights of the individual, others views were fueled by the dogma of the Catholic Church. Some talked critically of State/Territory versus Commonwealth powers.

The speech of Labor frontbencher (now Labor leader) Anthony Albanese is of note for its eloquence and passion: ‘This debate is hard – real hard,’ Albanese said. ‘It is hard because it is about death.’ He went on:

Most people are uncomfortable talking about dying … [Yet] this debate, as hard as it may be, is important. The outcome of this debate will reflect on our maturity both as a parliament and as a nation for it will determine the manner in which we seek to control each other’s lives.

I oppose this [Andrews] bill because I support human dignity. I oppose this bill because I support freedom of choice. I oppose this bill because I support civil liberties. I oppose this bill because my Christian upbringing taught me that compassion is important. I oppose this bill because modern medical practice should be open and accountable, not covert and dishonest…

I oppose this bill because I oppose the moral posturing of the Lyons Forum. I oppose the hypocrisy of those who say, ‘This debate is so important’ and then vote to debate it upstairs in sideshow alley.

Most importantly, I oppose this bill for one critical reason, and that is this. We have all accepted that this parliamentary debate should be a matter for our conscience.

How arrogant to then suggest that the ability to exercise conscience should be taken from a seriously ill patient who wants to die. There is nothing moral about our exercising a free conscience vote as members of parliament and then voting to deny to others the right to exercise their conscience.

What possible right do Kevin Andrews, Leo McLeay, Lindsay Tanner or Anthony Albanese have to have exercised Bob Dent’s conscience for him? It was his decision and he had a right to do that.

Of those who focused on territory rights, it was the Territory’s own Senator Bob Collins who led the way. Although a hostile opponent of the ROTI law, Collins was angry at the vilification of both the Territory and its politicians by Federal Parliamentarians. He was especially critical of Kevin Andrews and Senator Eric Abetz from Tasmania.

He was angry at Andrews for his audacity to think that ‘Territorians have no rights, only obligations’. Collins was also scathing of Abetz when the latter had tried to argue that ‘the Northern Territory parliament exists only by the grace and favour of the Commonwealth parliament. What the Commonwealth parliament gives, it can also take away’.

‘This’, said Collins, ‘from a senator from a state with about twice the population of the Northern Territory’s, and five times its representation in the House of Representatives and six times its representation here in the Senate’.

Mark Latham also supported both points made by Collins, but is best remembered for the following:

The euthanasia debate … should not be about forcing terminally ill people to judge life itself through the prism of someone else’s moral code. The only way religious questions have ever been successfully dealt with in public policy is by fostering choice.

Terminally ill citizens deserve nothing less than liberty in determining the manner by which their lives might end.

Other politicians focused more on their own moment in history.

Citing the eighteenth-century libertarian Edmund Burke in some detail, Barry Jones followed Burke’s lead, stating that he as ‘your representative’, ‘owes you, not his industry only, but his judgment; and he betrays instead of serving you if he sacrifices it to your opinion’. Jones’s mistake – and that of other politicians who drew on Burke – was to believe that it was appropriate for politicians to dismiss the ‘opinion’ of their electorates in favour of their own prejudices.

Sure, the political paternalism of Burke might have suited the uneducated, illiterate electorate of Bristol more than 200 years ago. But it is nothing short of arrogant to suggest that politicians like Barry Jones should do our thinking for us.

If Burke must be treated as the patron saint of politicians, then those who quote him should reacquaint themselves with the letterhead of the Whistle Blowers’ Society: ‘All that is necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men do nothing’.

Letters to the editor in the Sydney Morning Herald echoed my own feelings at what had just happened at the hands of the politicians:

I don’t understand why these evangelists of their own belief systems have the right to take away another individual’s right to end his or her own suffering.

This is the worst kind of politicking, far worse than acting out at Question Time, making errors with expenses or jetting around on fact-finding missions. I don’t care what ‘God’ a politician chooses to follow, but when his belief affects others I consider he has overstepped his already poor standing in the community.

My heart goes out to those who are suffering and those wanting to help them within the law.

Kevin Andrews fails to show for final Townhall debate

The phoenix that rose to become Exit International

As the fog lifted in the weeks following the success of the Andrews Bill, it became clear that while the ROTI Act was no more, the need for people to have access, if not to voluntary euthanasia, then to information about end-of-life options remained. Sick people still wanted to die. And so my focus changed. Political lobbying was over.

The previous twelve months had been as intense as they had been public and they had taken their toll on me. Yet I found that my work was just beginning.

I established the Voluntary Euthanasia Research Foundation (VERF) for people wanting to find out more and began a workshop and clinic program for people wanting to find out more that has since spread to all Australian capital cities and more recently to New Zealand.

One of the other challenges I took on in 1998 was to stand against Kevin Andrews in the federal election. Putting my money where my mouth was, I moved to Melbourne to stand in Andrews’ own electorate of Menzies, in Melbourne’s eastern suburbs.

During the campaign I worked closely with the Victoria Voluntary Euthanasia Society. Distinct from the poor effort they had made defending the NT legislation in Federal Parliament, they put their total support behind my challenge, and it gave me some insight as to what might have been possible when we were trying to defend the ROTI Act. If only.

Over $120 000 in donations came in, an amount that stood then as one of the highest records for campaign funds ever raised by an independent candidate. On election day we secured nearly 10 per cent of the primary vote.

While I’m not sure how worried Kevin Andrews was on that day, we were pleased that the Liberal seat of Menzies was forced to count preferences for the first time. This seemed suitable payback for the misery that his bill had caused, and this sentiment reminded me of another letter I had seen in the newspaper back in March 1997:

May I wish Mr Kevin Andrews a long and excruciatingly painful life.

With the 1998 election out of the way, my attention turned to the world stage and I flew to Zurich to attend the Conference of the World Federation of Right-to-Die Organisations.

There I spoke at length on the concept first put forward by Huib Drion of the Drion Pill.

Building on the conceptual work of Drion, I presented my own early thoughts on what the development of a ‘Peaceful Pill’ project might involve.

Given the unlikelihood of another VE law, I was already aware that new strategies were needed.

VERF, the foundation I established, was renamed Exit … the rest as they say is history.

Philip Nitschke, Amsterdam 31 January 2021

Aftermath of Menzies, 2007

Killing Me Softly documents the story of the Australian voluntary euthanasia movement from 1995 – 2011. Un updated version of the book will be published in 2021.

Killing Me Softly is available from Amazon in all countries.