March 25, 2024

Psychiatrists Must Face the Raw Reality

Psychological suffering Euthanasia for psychiatric patients ís a thorny issue. But you cannot solve it by not paying attention, argues Dutch Psychiatrist Menno Oosterhoff.

My colleague, psychiatrist Joeri Tijdink, recently questioned in NRC whether all the focus on euthanasia, due to mental illness, is healthy (19/3). Healthy for whom, I immediately thought.

For people with a euthanasia wish, who very often cannot be heard anywhere, it is very important and healthy for them to speak out about this. And it supports them when they find recognition in this from professionals.

That it is uncomfortable for psychiatrists is beyond dispute.

The core of our profession is to try to treat despair and suffering and not to go along with a death wish.

That that option is now available has not made our profession any easier.

When someone requests euthanasia, we are obliged to choose whether it is realistic and justified for the person to go for life, if that same life cannot be made bearable despite years of treatment.

That this is not an easy choice, I can immediately agree.

The first time in a conversation with a patient that I stopped trying to look for bright spots and instead acknowledged the darkness, I felt I was talking her to death.

But she said she found it a relief that I did not arrive with a dead end, with solutions that were not solutions.

So it’s not an easy choice, but it does patients’ justice.

Giving strength

Paying less attention doesn’t seem like a solution to me.

That by paying attention you only give people bad ideas I think is a ? statement.

The same used to be said about suicide.

Unbearable suffering is enough to make people think of death as a way out. They don’t need media attention for that at all.

However, paying attention and talking about thoughts of suicide or euthanasia can give people the strength to go on.

But the most important thing is that it is not we, as care providers, who decide whether it should be discussed, but the patients. They want to talk about it.

It is now more than 20 years since the euthanasia law was passed. This law allows doctors to perform euthanasia on request.

Today, 5 per cent of all deaths involve euthanasia, 8,720 times by 2022 . 115 times this was euthanasia due to mental illness.

I wouldn’t call that an epidemic.

It is time we found a way to deal with patients’ questions, and recognise that mental illnesses can also be incurable.

This does not mean that we are propagating or romanticising euthanasia.

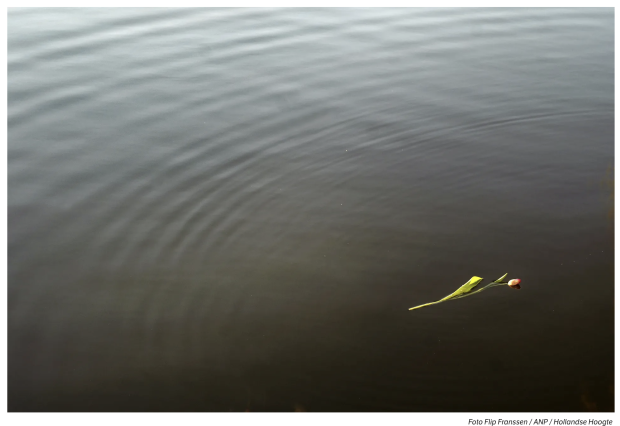

On the contrary, it is facing the raw reality that there are people who suffer unimaginably and for a long time because of mental illness, and that sometimes we can’t do anything about it.

I would like it that these people have somewhere to turn if they are considering ending their lives in the context of terrible suffering.

I think it is essential to our profession that we take people seriously, even if their questions make us feel uncomfortable.

I find it curious to think that psychiatry is the only medical specialisation capable of removing the unbearable suffering of patients. That is an illusion even if there were more money for the mental health sector, or if society was different, or if we had no waiting lists or if there were more support.

Nowhere to be heard

The raw reality is also, that suicide is the cause of death in 1 per cent of people.

About 90 per cent of these have a mental illness.

The risk of suicide in certain mental disorders is 8-12 times higher than in the general population.

The raw reality is also, that people with mental illness and a desire for euthanasia find almost nowhere within the mental health services that they can be heard.

They are referred to the Euthanasia Expertise Centre, which cannot handle this influx, which sometimes results in inhumanly long waiting times.

Medicine can sometimes cure, it can often relieve and it can always comfort.

Attention to euthanasia as a last resort even in cases of mental illness seems very healthy to me.

Psychiatrist, Menno Oosterhoff

Originally published in Dutch.