November 8, 2016

Nitschke Op Ed: Personal liberty at heart of right to decide how & when one dies

Philip Nitschke, The Dominion Post

OPINION: The recent antics of the New Zealand police in terms of the fake checkpoints and the subsequent searching of homes of elderly members of Exit International would be laughable were they not so serious.

The seemingly slapstick way police have gone about their intelligence-gathering has lowered the benchmark in how policing should be performed in a modern liberal democracy such as New Zealand.

To this end, public confidence in the police is affected.

Yet the actions of the police are serious and so are the consequences for those caught up in the covert ‘Operation Painter’.

READ MORE:

* Lawyers back group caught up in police euthanasia sting

* Police admit using checkpoint to target euthanasia meeting attendees

* Did police use booze checkpoint to target elderly women at euthanasia meeting?

* We know where you’ve been, police tell 76-year-old who attended euthanasia meeting

* Police seize voluntary euthanasia advocate’s helium balloon kit

Contrary to what some, such as former Labour MP Maryan Street, are claiming, the actions of the police have nothing to do with the health select committee’s inquiry into voluntary euthanasia: even though some of the Exit members involved have made submissions to, and are due to appear before, the inquiry.

Rather, the police raids and the confiscation of the drug Nembutal go to the site of a profound ideological struggle within the right-to-die movement globally.

At Exit International’s recent 20th anniversary conference at the State Library of Victoria in Melbourne, Susan Stefan, a United States law professor and author of Rational Suicide, Irrational Laws (Oxford University Press 2016), posited that ‘euthanasia’ – a good death – can be seen in two ways: as a medical treatment or as a civil right.

As a medical treatment, dying is controlled by doctors and euthanasia will only ever be afforded to a tiny minority of the population. That is to those who are sick enough and suffering badly enough to qualify to use such a law.In New Zealand, the law being pushed by the likes of Street is precisely this model as it “would [only] permit medically-assisted dying in the event of a terminal illness or an irreversible condition which makes life unbearable”.

“Sounds good”, I hear you say?

Not so fast.

In her new book Doing Us Slowly: What’s Happened to the Australian Voluntary Euthanasia Debate? cultural historian Dr Deb Campbell has argued that this medical model of voluntary euthanasia law reform defeats its own purpose because of its NOBA approach.

NOBA stands for Not Only But Also.

Not only must a person be terminally ill or suffering unbearably, But they must also get permission from the medical profession if they are to qualify to use the law.

According to Campbell, “this manipulation of the discussion of [euthanasia] into one where someone else must give their consent for my death is a fundamental repudiation of every tenet of doctor-patient relations, and of concepts of personal liberty and patient care prevailing”.”In all other situations, I choose what I do, provided I harm no one else, but not here.

“NOBA advocates seek to keep effective control of my death and yours in their hands, not to allow us real personal power.”

The Exit members who have had their Nembutal confiscated by police are caught in the middle of this problem of medical gate-keeping of an individual’s right to control the circumstances of their own death.

This is why they had their Nembutal hidden away at home in the first place.

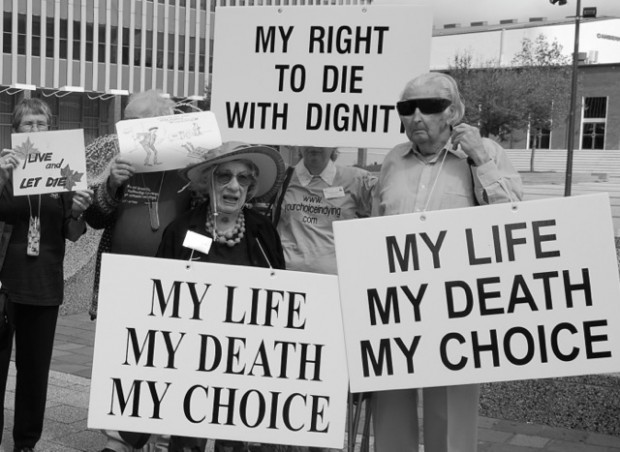

These Exit members are geriatric civil rights activists sine qua non.

If euthanasia is a civil right that is afforded to all rational adults of a certain age (let’s say 70 years here for the sake of argument), then a bottle of Nembutal locked away in a cupboard at home is its personification.

That bottle is a deeply-personal insurance policy for the future.

No medical hoops need be jumped through. One’s last days are guaranteed free from the type of red tape that characterises the implementation of right-to-die laws.

Quite literally, these elderly New Zealanders had moved beyond the law; or rather, beyond the need for euthanasia law reform.

Even though they have broken one law by importing this Class C drug, these senior citizens have been sitting pretty in the knowledge that they are prepared for what lies ahead: regardless of whether or not they find themselves with a future terminal diagnosis.

This is why the loss of the Nembutal by those Exit members whose homes were raided has been so traumatic, and infuriating.

They tell me they are not only humiliated by police intrusion on their privacy but that their personal dignity is in tatters.

There is something deeply cruel in depriving an elderly person of such a fundamental human right.

Any euthanasia law – and this remains hypothetical – will require these Exit members to have to rely on others. They would have to Not Only be sick, But Also seek medical permission if they are to die ‘well’.

The past 20 years of political stagnation on this issue suggests that the stars are far from aligned in the New Zealand skies.