December 29, 2024

Never before has there been so much public focus on self-determination

Suicide capsule ‘Sarco’, Middel X – ‘Never before has there been so much public focus on self-determination around death as now’

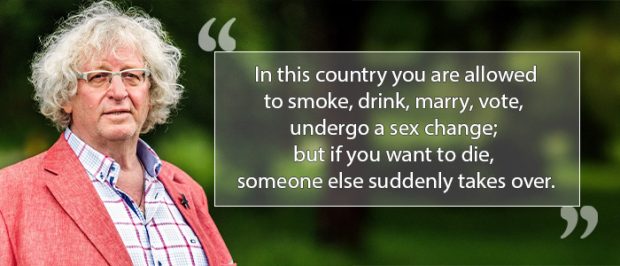

Jos van Wijk never minced words: one’s own dying, the 70-year-old believes, is a private matter. No one else needs to interfere with that.

Van Wijk made his conviction his work; until 2023, he was chairman of Coöperatie Laatste Wil (CLW), founded in 2013 with the aim of legally providing a humane means of suicide.

It is not that far yet: this year, several CLW members were in court for allegedly providing the ‘Middel X’ recommended by the cooperative. Some of them were convicted of assisted suicide – which carries a maximum prison sentence of three years.

‘Let me start by saying that I’m a baby boomer,’ Van Wijk said in court in April – from the generation that was “spoon-fed” “responsibility and self-determination”.

‘About smoking, drinking, sex change and getting your driving licence you can decide for yourself, but not about your end of life.’ He was given a four-month suspended prison sentence for participating in an organisation with assisted suicide as its goal.

Van Wijk interpreted a sentiment that is widely held. The group that wanted to be ‘master of their own belly’ in the late 1960s has grown old and also wants to decide when and how to die.

A representative survey by the Dutch Voluntary End of Life Association (NVVE) recently showed that 65 per cent of the population believes that people should be able to decide to end their lives themselves if they feel it is ‘complete’. In 2017, the previous time a similar survey was conducted, the figure was 57 per cent.

After the lawsuits over drug X, the next controversial development presented itself this autumn. In Switzerland, where rules around assisted suicide are more lenient, someone died for the first time in a Sarco, a suicide capsule developed by Dutch-based doctor Philip Nitschke that works with nitrogen.

Coöperatie Laatste Wil called on politicians to also ‘allow the use of the Sarco in a safe environment’ in the Netherlands.

Jos van Wijk, former President CLW

Never before has there been ‘so much public focus’ on self-determination around death, writes Stichting de Einder in its year-end newsletter.

They should know: the Einder was founded back in 1995 with the aim of enshrining the ‘right to die’ in law. Psychiatrists debated this summer about euthanasia for mental suffering, which is increasingly being granted. Is this not stretching the limits of the euthanasia law too far?

A working group will consider new guidelines in 2025.

In politics, on the initiative of D66, work has been going on for years on a Completed Life Act, aimed at giving older people the option to die when they feel they have lived their lives – including people who do not qualify for euthanasia according to the legal criteria.

The call for more control over dying dates back to the 1980s. In 1991, civil law professor Huib Drion published an opinion piece in NRC advocating that the elderly be allowed to decide how and when to die – that option was known for years as Drion’s pill.

‘If there are so many people who want that,’ Drion wrote, ’why shouldn’t they be allowed?’

There was no euthanasia law at the time, but the practice was in line with what came into effect in the law that came into force in 2002.

Doctors must determine whether patients are suffering unbearably and hopelessly, that law stated. If that is the case, only they may grant euthanasia.

Through court cases and legal proceedings, further context was given to the law in the years that followed: for instance, there must be suffering with a medical cause.

Even when the law went into effect, there was a movement ‘of people who found it too limited for all sorts of reasons’, says Johan Legemaate, professor emeritus of health law at Amsterdam UMC and the University of Amsterdam, and involved in recent evaluations of the euthanasia law.

They found, for example, he says, that you should not be dependent on your doctor when choosing to end life, and that ‘medical suffering’ should not be the only criterion. According to Legemaate, even then there were people who felt that requests for euthanasia because of a ‘completed life’ should be honoured.

Because of that sentiment, the issue has been prominent on the political agenda since 2016. D66 finally tabled a bill in 2023. If someone aged 75 or older feels that their life is complete, they could go to a so-called end-of-life counsellor, the bill states.

Three conversations would have to be held over a minimum period of six months, after which the end-of-life counsellor – who does not have to be a doctor – could offer assistance in dying. In early December, experts answered MPs’ questions about the bill in a round-table discussion.

This showed that there are still many hurdles to be taken. For instance, experts criticised the strict age limit of 75 years. Isn’t it discriminatory? Isn’t this actually saying: at 75, you have lived long enough?

Els van Wijngaarden took part in the roundtable discussion. She is a care ethicist and associate professor at Radboudumc in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, where she leads a research group looking at ageing and autonomy around dying, among other topics.

Van Wijngaarden is critical of the Completed Life Act, mainly because in conversations with elderly people and their loved ones, she repeatedly sees that a death wish is ambivalent. ‘Not infrequently, people are limping on two minds – the death wish and the wish to live often coexist.

You often hear as an argument for more self-determination that people do not want to suffer, and also that they do not want to become victims of poor care.

So should we rig up a scheme where you might put pressure on people in a vulnerable situation to die earlier?’

A completed life act, pill or more self-determination may reassure people, she says, ‘but death will never be something simple’.

Lawyer Tim Vis, who assists several defendants in Middel X cases and other assisted suicide cases, is happy that the completed-life law has been ‘awakened’, but thinks the proposal does not go far enough.

He argues that people who want to die should not have to rely on doctors or other practitioners.

‘As a lawyer, I struggle with the current situation. We are asking doctors or end-of-life counsellors to resolve something that is an existential choice of the human being. And moreover: a human right.’

Together with Cooperative Last Will, Tim Vis has been waging a lawsuit against the state for years to remove assisted suicide from the criminal law. In 2022, CLW lost in the first instance. The state is obliged to protect citizens’ lives, the court emphasised then.

According to the court, that means, among other things, that the state must try to prevent vulnerable people from ending their lives on a whim. CLW and Tim Vis have appealed; the case will be followed up in 2025.

Johan Legemaate sees legal possibilities for broader legislation on assisted suicide. ‘The European Court of Human Rights has made quite a few rulings on end-of-life decisions, and these indicate that as a national legislator you could well go a bit further than the current euthanasia law.’

One might wonder, says Legemaate, whether it is necessary to add something to the current system. ‘Is a large group of people left out in the cold? Maybe not.’

It is unclear how many older people have the wish to die but do not qualify for euthanasia. However, it may be that the government wants to provide more room for self-determination on principle. ‘That could be a reason for additional regulation.’

Stopping eating and drinking

Fransien van ter Beek, president of the Dutch Association for a Voluntary End of Life (NVVW), does not think it is important in this discussion how big the group involved is.

‘Do you need to know how many believers there are to be in favour of freedom of religion?’ As the medical profession gets better and better at eliminating disease, we are getting older.

‘And there is a category that does not want to get that old and is also not eligible for euthanasia.’

She sees the demand for more self-determination as a driver of medical progress. ‘You can also see in birth care that attitudes have changed in recent decades. We no longer consider suffering necessary: pain management is used more and more.’

This year, Cathelijne Verboeket-Crul published Letting go of life, a book about dying.

At the hospice where she works, she also accompanies people who consciously stop eating and drinking in order to die that way.

She wets their lips to reduce the sensation of thirst, and ensures the most comfortable end of life possible. It is an intensive but legal method for patients and practitioners.

This year, a new ‘handbook’ came into force at this practice, which for the first time no longer has an age limit (previously it was 60).

Verboeket-Crul believes society benefits from an honest conversation about dying. ‘About the fear of death, fear of suffering, about our negative image of old age.’

There are no ready-made solutions, she says. ‘We are in a fire culture where everything has to be done as quickly as possible and exactly the way people want it.’ Is death the solution or should we as a society work towards a greater sense of community, she wonders.

‘We have set up our society in a very individualistic way and our healthcare is getting more and more stripped down – and it’s not getting better as it stands.

Death is sometimes a good alternative to admission to a nursing home. If we lived in a community where you matter in old age, we would treat the elderly differently.’