July 26, 2022

Foreigners fret over stricter Swiss rules on assisted suicide

Foreigners fret over stricter Swiss rules on assisted suicide

The Swiss Medical Association’s new guidelines for assisted suicide will hamper access to this practice and upset foreigners who seek to end their lives legally in Switzerland.

This content was published on July 26, 2022 – 09:00 July 26, 2022 – 09:00

“Have you heard about it?” read the subject line of the email Alex Pandolfo received from a friend in May this year. Attached was a newsletter titled “Worrying News from Switzerland” from the Australian assisted suicide organisation Exit International.

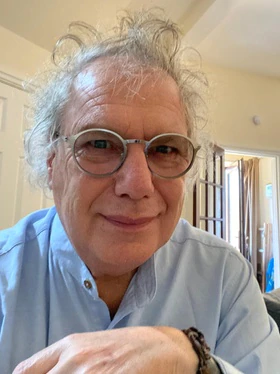

David Goodall, centre, a 104-year-old Australian scientist who died by assisted suicide in Switzerland, although he was not suffering from a terminal illness. Such cases, based on old age, might no longer be allowed in the future. © Keystone / Georgios Kefalas

The report contained the latest information on Switzerland’s new guidelines for assisted suicide. People seeking to end their lives should have two meetings – at least two weeks apart – with a doctor before the final decision.

Sixty-eight-year-old Pandolfo lives in the UK. When he was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer disease in 2015, Lifecircle, an assisted suicide organisation in Basel, gave him the green light and accepted his request for assisted suicide.

He plans to go to Switzerland when “the time has come”.

Alex Pandolfo

Under the old rules, he would have had to stay in Basel for just a few days to complete his plan, but the new ‘two-week-rule’ makes it a lot more expensive. “People who don’t have enough money will be put off by it,” Pandolfo told SWI swissinfo.ch.

Foreigners fret over stricter Swiss rules on assisted suicide – No assisted suicide for healthy people

How did this change come about? In May, the Swiss Medical Association (FMH) agreed on the revised guidelines for the “Management of Dying and Death” proposed by the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences (SAMS). The guidelines will be part of the deontological code doctors have to adhere to in the future and are as follows:

The physician must – other than in justified exceptional cases – conduct at least two detailed discussions with the patient separated by an interval of at least two weeks.

The symptoms of the illness and/or functional impairment must be unbearable, the severity of which is to be substantiated by a legitimate diagnosis and prognosis.

Assisted suicide for healthy persons is not medically or ethically justifiable.

Before, during, and after the assisted suicide takes place, the needs of the relatives and interprofessional care and support team must also be taken into consideration. Required support is to be given and must be documented.

Swiss doctors adopt tighter assisted suicide guidelines

This content was published on May 20, 2022 May 20, 2022 The new regulations have been criticised as too harsh and difficult to implement by assisted suicide organisations.

The SAMS’ guidelines External linkare not legally binding. But the fact that the Swiss Medical Association (FMH) has adopted and included them in the deontological code makes it possible to sanction violations.

The FMH is the umbrella organisation of all the Swiss medical associations and represents the interests of Swiss doctors, over 90% of whom are members of the FMH and must adhere to the deontological code.

‘Not tightened, but refined’

In 2018, SAMS which is a private research funding institution, enacted new medical ethical guidelines for the “Management of Dying and Death”. It laid down exactly what doctors should conform to when they perform assisted suicide.

The FMH, however, did not agree with the 2018 guidelines and rejected them for being too vague.

“The revised guidelines have not been tightened, but refined,“ says SAMS Secretary General Valérie Clerc.

Assisted suicide organisations adamantly reject the new guidelines. Medical doctor and Lifecircle president Erika Preisig is particularly upset about the ‘two-week-rule’ which she thinks is especially difficult for foreigners.

Even though Lifecircle offers the first meeting online, Preisig thinks it could still be a problem for some people. “Most of our patients are elderly who may not know how to conduct an online meeting.

Some don’t even have a smartphone,” she notes. That means they would be obliged travel to Switzerland two weeks before their scheduled assisted suicide.

And this would be particularly expensive for people with disabilities as they would have to cover the cost for their special care during the two weeks between consultations.

“The guidelines allow for exceptions, but not if people cannot afford to stay in Switzerland for two weeks,” says Clerc told SWI swissinfo.ch. “Exceptions are made if a person is close to dying or if their suffering is so unbearable that a long wait for their assisted suicide would seem intolerable.”

Switzerland has long been criticised for its stance on assisted suicide. Critics say the Swiss approach promotes “suicide tourism”.

Was the ‘two-week-rule’ introduced to reduce the number of “suicide tourists”? SAMS merely states that the guidelines do not differentiate between Swiss nationals and foreigners at any point.

‘Physicians turn into gods’

Travel expenses are not the only problem. Thirty-year old Aina from Japan suffers from a rare neurological condition.

She has also been the given green light for her assisted suicide. But she worries about the rule which states that the “severity of the suffering is to be substantiated by a legitimate diagnosis and prognosis”.

People who seek assisted suicide in Switzerland are required to explain in their own words the severity of their suffering and the reason why they want to die. This letter must be submitted in addition to their medical record.

Aina’s illness is so debilitating that she cannot stand up or walk and is completely reliant on her mother to get through every day of her life. Her condition is different from terminal cancer. She will not die immediately and will probably suffer for a very long time.

“If doctors use their own judgement to decide whether my illness meets the guidelines to use assisted suicide, what about my own right to decide?” she wonders.

“Nobody else but me can judge how severe my suffering is and how badly I want to die because of it, but me. These new guidelines almost turn physicians into gods.”

Assisted suicide: How a quest for death rekindled the will to live

The assisted suicide organisation Dignitas has a similar stance. In its newsletterExternal link it states that “the new guideline shifts from putting weight on the patient’s personal view as justification for a physician to support the request for assisted suicide towards a more medical-diagnosis-classification of suffering.”

It also says that “the medical reports and the internal documentation required by a Swiss physician will have to be even more detailed than before.”

Switzerland’s largest assisted suicide organisation EXIT told SWI swissinfo.ch: “The guidelines fail to recognise that psychosocial problems can also be a legitimate factor in wishing to end one’s life.”

Assisted suicide organisations believe that the ban on helping healthy people end their lives does not take into consideration that “the Swiss Federal Supreme Court and the European Court of Human Rights have declared the freedom to decide on the time and manner for every individual to end their own life as a human right.”

Opaque procedure

Assisted suicide organisations have criticised the “opaque procedure” of SAMS and FMH. EXIT spokeswoman Muriel Düby said that neither the Swiss medical fraternity nor the patients and assisted suicide organisations were given the chance to react to the new guidelines.

“Even after the draft was approved by the highest authorities of SAMS, it was still classified as secret.”

EXIT offers its services to Swiss nationals who live in Switzerland and abroad. In a meeting in June, the board members decided to continue as usual despite the new guidelines

Preisig and other representatives of assisted suicide organisations worry that more doctors will be hesitant to perform assisted suicide in the future.

Pandolfo says he would have taken his own life out of fear for his future a few years ago if he had not been given the green light for assisted suicide.

“The idea of assisted suicide has improved my quality of life because I knew that I could end my life whenever I wanted.”

At the end of the day, it prevents suicide. “I think Switzerland makes a big mistake [by introducing these new guidelines].”

Translated from German by Billi Bierling