December 16, 2021

A 3-D Printed Pod Inflames the Assisted Suicide Debate

A 3-D Printed Pod Inflames the Assisted Suicide Debate

The pod, known as Sarco, was conceived as a way for people to end their lives without involving a doctor. A plan to introduce it in Switzerland has raised alarm even among right-to-die advocates.

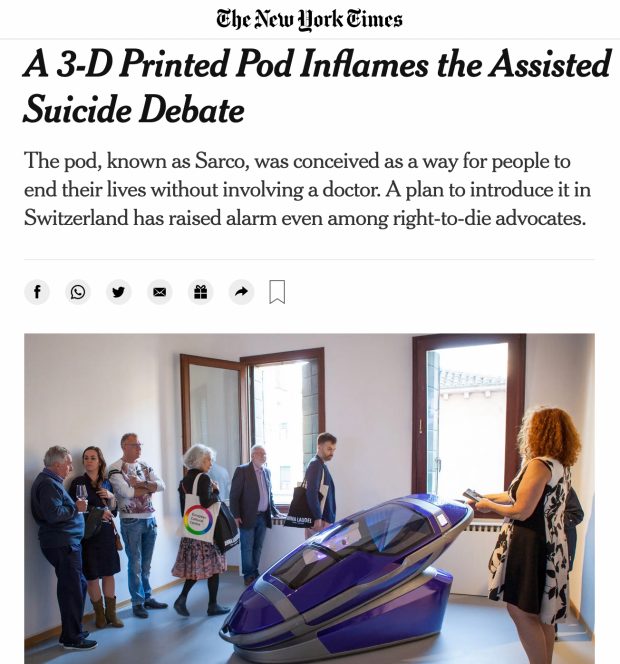

For years, a sleek, pod-shaped suicide machine called Sarco has been a striking sight at museums and funeral conventions.

Now the creator of the pod is saying he is ready to take it beyond the showroom and make it available for 3-D printing next year in Switzerland, which has permissive laws on voluntary assisted suicide.

The announcement by the inventor, Dr. Philip Nitschke, has unsettled even some of the most ardent right-to-die advocates, inflaming the debate.

Dr. Nitschke, an Australian doctor who has been a supporter of assisted voluntary suicide for decades, said this month that he hoped to start sharing the 3-D printing program for the machine, which is designed to cause death as it fills with nitrogen, replacing the oxygen inside.

He said he was aiming to introduce it in Switzerland in early 2022 after a lawyer hired by his nonprofit organization, Exit International, found no conflict with Swiss law. But the announcement, which he made in interviews and on the organization’s website, added to a growing debate over whether the online distribution of suicide information and materials encourages people to end their own lives when they might not otherwise seek to do so.

A 3-D Printed Pod Inflames the Assisted Suicide Debate

In Britain, where an assisted dying bill is being reviewed in Parliament, Dr. Stephen Duckworth, the founder of Disability Matters Global, wrote in The Independent that he was “appalled” by Sarco.

Dr. Duckworth, who has pressed for safe laws emphasizing personal choice and control of the dying process, added that he could not support it, “nor am I aware of any credible assisted-dying campaigner who does.” Sarco, he said in an interview, would “deprive users of human connection and replace it with a lonely virtual-reality experience.”

He also raised concerns about safety. “What if it is accessed by someone not in their right mind?” he said. “Or a child? Or if it is used to abuse others? What if it doesn’t result in immediate or peaceful death and the individual is left alone without any recourse to call for help?”

Dr. Charles D. Blanke, an oncologist and a professor at the OHSU Knight Cancer Center in Portland, Ore., who has studied data on physician-assisted dying, said breathing in nitrogen causes a rapid death. But he cautioned that it is untested, including as an alternative to lethal injection in capital punishment.

“It is not at all clear that nitrogen inhalation would bring a peaceful death,” he said, contrary to Dr. Nitschke’s claim that death comes quickly after a brief euphoria.

The law in Switzerland, where about 1,300 people sought help from right-to-die organizations in 2020, requires confirmation that people seeking to end their own lives are of sound mind and reached the decision without pressure from anyone with “selfish” motives. Then a doctor writes a prescription for sodium pentobarbital, the lethal medication used there.

Sarco would bypass that step because it does not require a prescription for a drug.

Some Swiss right-to-die organizations have distanced themselves from Sarco. Exit, which offers living wills, counseling and end-of-life care, and is unaffiliated with Dr. Nitschke’s similarly named nonprofit, said it does not see Sarco as an alternative to physician-assisted suicide. Another group, Lifecircle, said “there is no human warmth with this method.”

Dignitas, a clinic near Zurich, said sodium pentobarbital “is approved and supported by the vast majority of the public and politics.” Pegasos Swiss Association said it was in discussion with the Sarco team but wanted further clarification about the device.

Others who have studied the ethics of voluntary assisted suicide welcomed the debate that Sarco has inspired. Thaddeus Pope, a bioethicist at the Mitchell Hamline School of Law in St. Paul, Minn., said the debate about Sarco could lead to a new way of looking at end-of-life options, including by legislators.

“That might be bigger or more important than the actual Sarco itself,” he said, adding that Dr. Nitschke was “illustrating the limitations of the medical model and forcing us to think.”

“There are a lot of people that live with illnesses or conditions that they don’t want to live with, but they don’t qualify for medically aided dying where they live,” he said. “If he really goes forward with it, this may get the nonmedical approach to hastening death some more attention.”

Dr. Nitschke, 74, has years of experience with assisted suicide. In the 1990s in Australia, he developed a machine that allowed his terminally ill patients to initiate their own deaths by administering a lethal medication with the touch of a computer key. This was the same era when Dr. Jack Kevorkian was promoting — and being prosecuted over — an assisted suicide device in the United States.

Dr. Nitschke said he was inspired to create Sarco by the death in 2012 of Tony Nicklinson, a British man who suffered from so-called locked-in syndrome and whose request for help in ending his life had been rejected by a panel of judges.

He said he had taken steps to ensure that anyone using Sarco would be doing so voluntarily. Users can initiate the nitrogen flow only after stating their name and where they are, and that they know what is about to happen. That process is filmed, he said, and a copy is provided to the coroner.

“You say goodbye to everybody and climb in,” Dr. Nitschke said. “The idea is you are going, and they are staying.”

Dr. Nitschke worked with designers in the Netherlands, where he lives, to produce a Sarco prototype in 2017 that has since been exhibited in museums and funeral fairs in Amsterdam and Venice.

This article has been edited for length.

Note – the criticisms made in this article have been responded to by way of Open Letter by Philip Nitschke published 8 January 2022.