January 1, 2021

The Exit Bag’s Role in Australian Law Reform

The Exit Bag

The Exit Bag’s Role in Australian Law Reform is a little-known story.

The use of plastic bags to bring about a peaceful death is not new.

Derek Humphry outlines the practice in his book Final Exit, but the use of a specific ‘customised’ bag for the purpose of ending life was first described in a brochure written by Canadian John Hofsess in 1997.

The Right to Die Society of Canada was the first group to market the bag and an instruction booklet in 1997 and the bags have since been widely distributed around the world.

Many Australians have ordered them by mail, paying US$46 for the kit. But all this came to an abrupt end in 2001 when the US anti-euthanasia campaigner Wesley J. Smith visited Australia.

With sympathetic front-page coverage from the staunchly Catholic journalist Denis Shanahan, The Australian revealed the importation of the Canadian bags into Australia was occurring.

Florid in style, Shanahan’s article demonstrated only an elementary understanding of the science of the bags: ‘The suicide bags, reminiscent of the Khmer Rouge’s shopping bag executions in Cambodia’s killing fields, are mailed directly to applicants in a plain white envelope’.

Intended or not, the factual errors and sensationalist slant of the story were enough to create a moral panic; one that led Justice and Customs Minister Chris Ellison to call for an urgent report from Customs to determine whether there were grounds to prevent the importation of the bags. The very next day Ellison was reported as saying: ‘I would remind anyone considering the importation of these kits that aiding and abetting or inciting the killing of a person is a criminal offence in all states and territories’.

All this occurred within a week of Shanahan’s article, confirming that the government can respond quickly when it wants to.

The Exit Bag’s Role in Australian Law Reform, as instigated by Chris Ellison, spelt the end for the importation of the Canadian bag.

While there was some doubt whether Customs could actually detect the arrival of such bags, the threat was enough to put an end to the trade as Exit advised its members of Ellison’s warnings on the issue.

When Exit was contacted by a number of elderly members who said they had changed their minds about ordering the Canadian bag, we set about developing our own. Modelled on the Canadian version, the Australian Exit Bag is made of thick plastic and has an adjustable soft-neck opening consisting of material with elastic attached.

It is important to note that while an Exit bag may not look very attractive, it is a reliable method of ‘self-deliverance’. A low oxygen death is peaceful. More common ‘hypoxic’ deaths are those caused by a lung infection (pneumonia – the old person’s friend) or the sudden depressurisation of an airplane, where whole aircrews occasionally die as if in their sleep.

This is not a violent death from a mechanical obstruction of one’s airway. A person using an Exit Bag breathes easily with the oxygen concentration in the inhaled air decreasing until unconsciousness and death result.

To suppress the arousal produced by the raised concentration of carbon dioxide in the bag and low oxygen levels, sleeping tablets are taken prior and the bag positioned so that it only functions once sleep comes.

For an Exit Bag to work as planned, skill is required.

In the United States and Canada, the bag is often used in combination with helium gas. This gas improves the efficiency of the bag, since the helium displaces the oxygen so that hypoxia and death occur in a matter of minutes. In America, disposable helium canisters are readily available in supermarkets, but in Australia helium is only available in leased high-pressure cylinders.

The resulting paper trail can legally complicate the process.

The Exit Bag’s Role in Australian Law Reform is a minor but interesting footnote to the history of the global right to die movement.

*Note this article was first published in 2005. The technical information it contains is no longer correct.

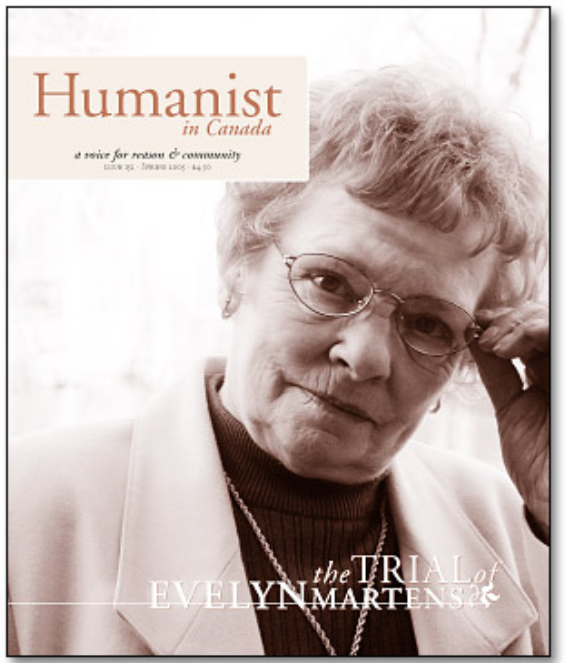

Evelyn Martens & the Canadian bag

The acquisition of helium is not the only legal issue that should be considered in regard to the use of plastic bags to cause death.

In Canada – the ‘home’ of the customised Exit Bag – a prominent member of the Right-to-die Network (the organisation that distributes the bags) has recently been charged with two counts of assisted suicide.

Evelyn Martens, a 74-year-old pensioner, was formally charged with assisting and counselling two people to suicide in January and July 2003. They were a 64-year-old former nun, Monique Charest, and 57-year-old teacher, Leyanne Burchell of Vancouver.

The evidence gathered against Martens included the discovery of a supply of helium, plastic tubing and plastic bags to these women.

Martens was charged following an undercover operation whereby a Canadian policewoman posed undercover as the goddaughter of Monique Charest.

The policewoman recorded Martens describing the death and how she had been present.

In evidence presented to the court, Martens is alleged to have told the policewoman, ‘I made sure that this was what she wanted.’

Evelyn elected to be tried by a judge and jury, and her trial commenced in October 2004. She would be found not guilty.

At the meeting of the NuTech group in Seattle in January 2004, almost all the Americans present thought that using the bag with helium gas represented the method par excellence for a peaceful death.

Indeed, the bag is the predominant method of ‘self-deliverance’ recommended by the US VE-support group, Caring Friends.

Despite this, however, many people consider dying with a plastic bag on their head to be rather undignified. This view is often heard at my workshops, even by those who have a clear understanding of the reliability and peace of the method. ‘I don’t want to be found looking like that’ is the common response.

While these concerns are based on aesthetics, not physiology, they are powerful disincentives when it comes to using an Exit Bag.

In the documentary Mademoiselle and the Doctor, Lisette Nigot discusses this point in some detail:

I didn’t invent it, but Philip had presented the plastic bag at one of his workshops… I looked at it with interest. I said, ‘I would never use a thing like that’…but my interest had been awakened and I said, ‘Mmm, I can make one’…

The bag is one of the many bags I have in which I buy my parrot’s seeds…I stitched a very large hem and I left an opening… Now, I don’t like it at all. I don’t think it’s nice…it’s not a nice way to die. But apparently it’s a very good way and you never miss…[For me] the bag is really the last option.

And this is a common sentiment.

While American activists continue to promote helium-filled plastic bags, members of Exit International prefer to seek other means. Exit’s own research shows that only 0.3% of our members would prefer to use an Exit Bag than the Peaceful Pill (88.6%). You will find an in-depth discussion about the Peaceful Pill in chapter 11.

See also: Shanahan, D. (2001) Mail order suicide kit. The Australian, 20 August.